Literature, science fiction, and the fringe

Literature, science fiction, and the fringe

Literature, science fiction, and the fringe

Literature, science fiction, and the fringe

by Steven L. Peck

Jorge Luis Borges’ Ficciones are dense, almost unapproachably so. Each of the Argentine maestro’s short stories is a tightly-wrapped morsel that resists rapid digestion. Independent contemplation is required to profit from a reading of Ficciones: a story presents an idea and working through its implications is a follow-up exercise left to the reader.

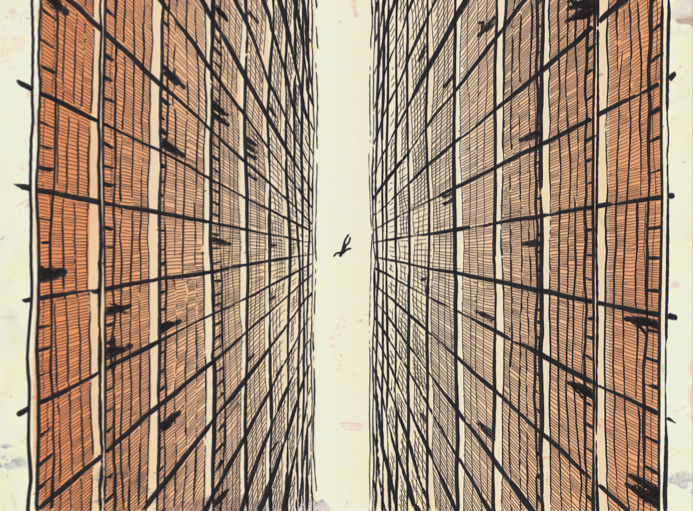

Steven L. Peck’s A Short Stay in Hell is the result of such an exercise. The 2009 novella, released by Strange Violin Editions [1], works the ~seven page Borges story “The Library of Babel” (1941) into one hundred pages of fast-reading, first-person narrative. Peck’s objective is to bring the nigh-incomprehensibly large scale of Borges’ Library into focus for us small humans. Calling its scale “astronomical” would be a criminal understatement — the Library’s contents far exceed the scope of our universe.

Put simply, the Library holds every possible string of characters, leather-bound in uniform 410-page volumes. It’s a manifestation of a mathematical concept in a field that would later be named information theory. Given a fixed-length data segment (410 pages, 40 lines per page, 80 characters per line) and an encoding scheme (consider only the Latin alphabet and standard punctuation marks), what can be expressed? Well, everything. As Borges puts it, “when it was announced that the Library contained all books, the first reaction was unbounded joy. All men felt themselves the possessors of an intact and secret treasure.” [2]

There is, of course, a catch. How large is this “information space,” this Library? It’s large. Really large. The integer representing the number of books it holds is itself over a megabyte. The Library is hard-to-wrap-your-head-around large, which is where Peck comes in to help.

A Short Stay in Hell follows a man consigned in death to an indefinite stint in the Library of Babel, terminating only when he locates his biography among its stacks. From this man’s perspective, Peck details the mechanics of existence in the Library. What you eat, who you eat it with, how “indefinite” works when you are a fleshy corporeal entity. What searching really entails when adrift in such a vast sea of noise.

In “The Library of Babel,” Borges primarily explores the gap between the coherent and the meaningful. “For while the Library contains all verbal structures, all the variations allowed by the twenty-five orthographic symbols, it includes not a single absolute piece of nonsense.” This is true, perhaps, in an abstract, mathematical sense, but functionally irrelevant to a searcher without the keys to decrypt such arcane knowledge.

Aj;kLJippOinfeTImNB2uyS@.jHnMBVFghT/.hk

%hKh’2jh<b YblZI@)m$n@gDE#2B/„lhqWXud7 (pg. 27)

Peck applies this scientific lens to his rendition and focuses on the much larger gap between the possible and the coherent. For practical purposes, the overwhelming majority of content in the Library is gibberish. It may take a year of searching to find a coherent sentence and a millenium to find a single paragraph. Orders of magnitude stack up and exponential growth is unintuitive to our incorrigibly linear minds. Thus, Peck’s Hell is formed.

Entertaining and succinct, A Short Stay in Hell is a well-conducted thought experiment that gets its point across without overstaying its welcome. It’s no literary masterpiece but it doesn’t try to be one — it leaves the virtuousity to Borges’ original and instead focuses on giving it a proper speculative fiction treatment.

Attribution: Steven L. Peck, via Mormon Artist

[1] Strange Violin Editions is an independent imprint serving the niche readership of “Mormonism-related books that fall outside the parameters of LDS orthodoxy.”

[2] “The Library of Babel,” by Jorge Luis Borges (1941), translated by Andrew Hurley and made available by Evergreen State College.

◂ prev: Feb 2023 |

next: Jun 2023 ▸ |

The Last Free Man and Other Stories

(2019)

by Lewis Woolston

|

Of Human Bondage

(1915)

by W. Somerset Maugham

|