Literature, science fiction, and the fringe

Literature, science fiction, and the fringe

Literature, science fiction, and the fringe

Literature, science fiction, and the fringe

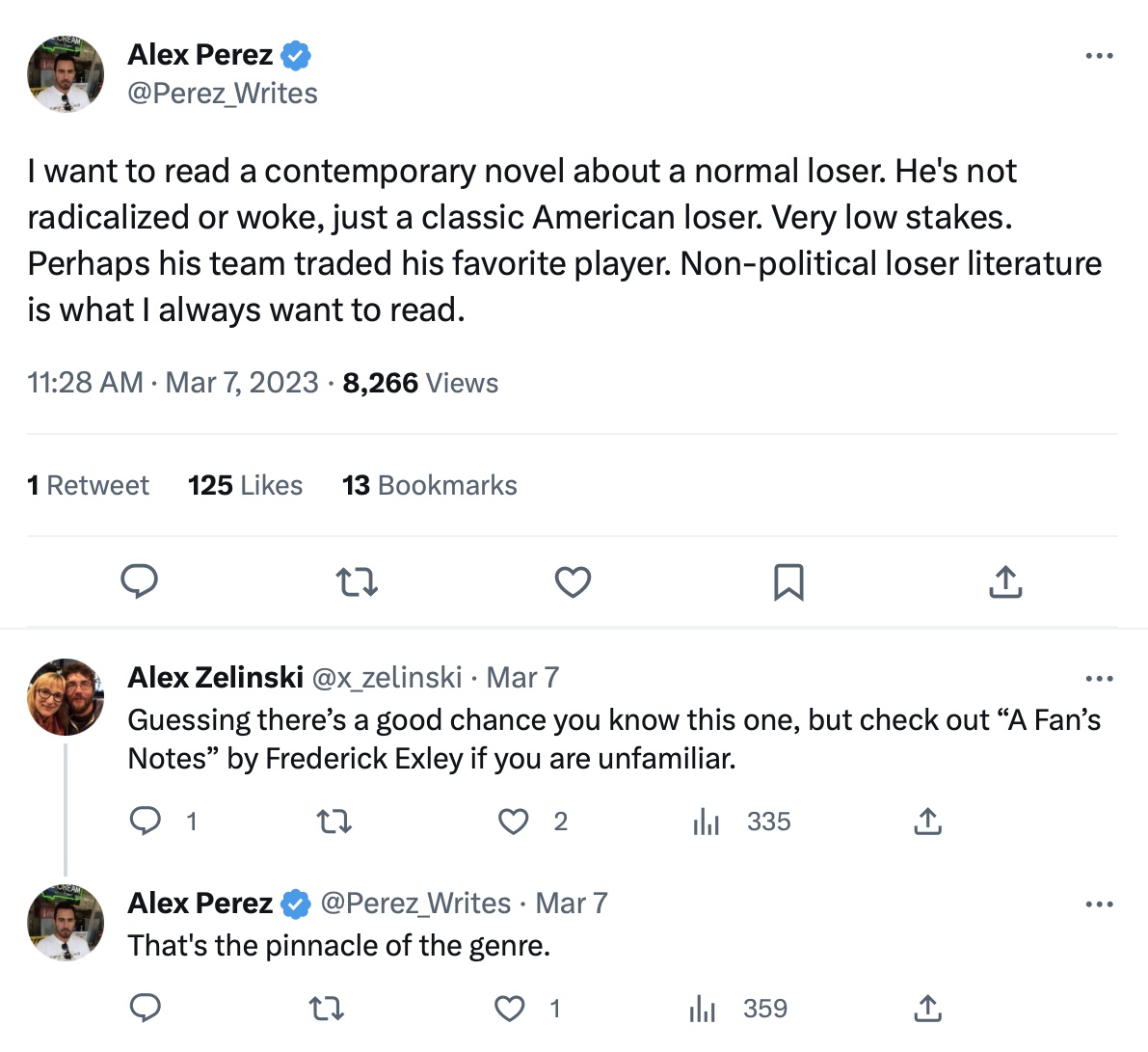

by Frederick Exley

This might be it: the ultimate, unabashed, unfiltered post-war American loser novel. Is that what you were looking for?

Framed as a memoir, Freddy Exley, or Ex, is a maladjusted alcoholic who leans on the New York Football Giants as his rock in a world that won’t accommodate him. Thirty something at the time of writing, he’s a Watertown, NY local who grew up in his father’s hometown hero shadow. This shadow represents the one thing that matters to Freddy: the separation between the exceptional and the mediocre, between the players and the fans.

I had gone each lonely Sunday to the Polo Grounds where Gifford, when I heard the city cheer him, came after a time to represent to me the possible, had sustained for me the illusion that I could escape the bleak anonymity of life. (pg. 231)

The New York Football Giants at the Polo Grounds in the 1950s, courtesy of Football Forum

Both author and subject of A Fan’s Notes, it’s unclear how much of the Ex we see is the man and how much is fabricated—the broad strokes of his Wikipedia article line up with the story. Born to a local football star but himself no star athlete, Ex hopes to reach salvation by contributing to posterity with his writing. For inspiration he forms an all-too-familiar parasocial relationship with USC classmate and Giants all-star Frank Gifford who unwittingly bears Exley’s self-image each Fall Sunday. When Gifford earns praise for his exploits on the field, Ex is able to entertain notions (delusions?) that he, too, is worthy of the adoration of the crowd.

But the dream of fame had been real enough: I had wanted nothing less than to impose myself deep into the mentality of my countrymen, and now quite suddenly it occurred to me that it was possible to live not only without fame but without self, to live and die without ever having had one’s fellows conscious of the microscopic space one occupies upon this planet. (pg. 99)

On style: Exley’s writing is wordy, learned, witty, and frank. Structurally, A Fan’s Notes is a matryoshka of digressions that always come back around to the original point in time. This nested structure stretches down into paragraphs and often sentences in the form of an adept storyteller who never loses sight of the big picture but doesn’t spare any microscopic detail. Frustrating to hold onto so many loose ends at the start, Exley executes an elegant endgame as nested arcs are merged one by one back into the main trunk of the story. Reading it requires an attention span beyond that demanded by most books published since.

Courtesy of Biblio

Picking up A Fan’s Notes the better part of a century after it was published, the most interesting element to me was the interaction between the dysfunctional man and a functional society. This juxtaposition marks the book as an unmistakable product of its time. Despite bungling every opportunity granted him, Ex never truly lacks friends, romantic partners, or gainful employment. He is many pitiful adjectives but atomized he is not.

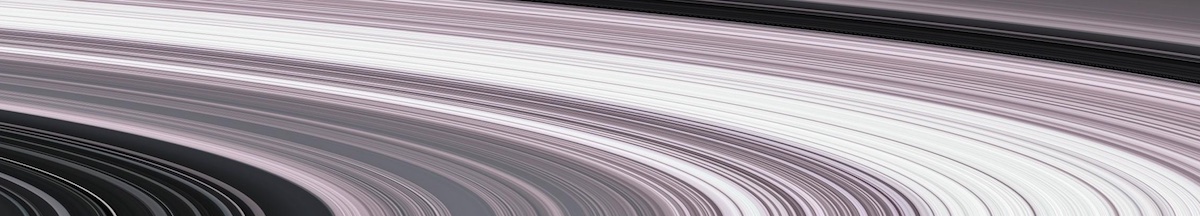

In this way, A Fan’s Notes is the American alternative to Osamu Dazai’s No Longer Human (1948). The Budweiser to its sake. The Japanese I-novel—adored by weebs, college students, and internet types these days—explores similar themes in a semi-autobiographical form factor, written by an adrift neurotic alcoholic who lucks his way into gainful employment as an artist and whom women seem to throw themselves onto. While both novels are superficially about how wrong things are going for the protagonists, it’s hard also not to see how much goes right for each.

If Exley had come of age in the new millennium instead of the 40s and 50s, would he still have been able to write A Fan’s Notes? Probably not—I’d wager the bulk of his frenetic creative energy would have been spent shitposting on the internet, consuming deranged pornography, or screaming into a video game headset. He might have still struggled with alcoholism but he’d be imbibing in solitude to the glow of a computer monitor instead of on a bar stool.

Depressive as it is, A Fan’s Notes is also a love song to a bygone era of functional social sphere. Ex’s struggle is characterized by second, third, fourth, and fifth chances. It is characterized by a loving family, a low cost of living, a favorable and forgiving job market, and a functional public mental health system. If against the odds a modern Exley were able to marshal the focus necessary to write an opus like A Fan’s Notes, the life he was chronicling would have undoubtedly been very different.

Always trust recommendations from literary e-celebs.

As an aside, another thing struck me as particularly odd: no mention of the offseason! Football is a flash in the pan even with today’s protracted seasons—in Exley’s day the span between kickoff on opening day to the last seconds of the championship game was barely three months. Fandom IRL is characterized by interminable droughts whereas Exley portrays it like an ever-present part of his life. While not always mentioned, tacitly the Giants are always present, and there’s no great elation at the start of a new season nor despondency at one’s conclusion.

◂ prev: Jun 2023 |

next: Apr 2024 ▸ |

Hard Rain Falling

(1966)

by Don Carpenter

|

Thirteen Cents

(2000)

by K. Sello Duiker

|